Dame Elizabeth Anionwu: UK’s Celebrated Black Nurse — How Nigeria Lost a Girl Who Could Have Arrested the Ravaging Sickle Cell Disease in Africa

Lawrence Oladotun

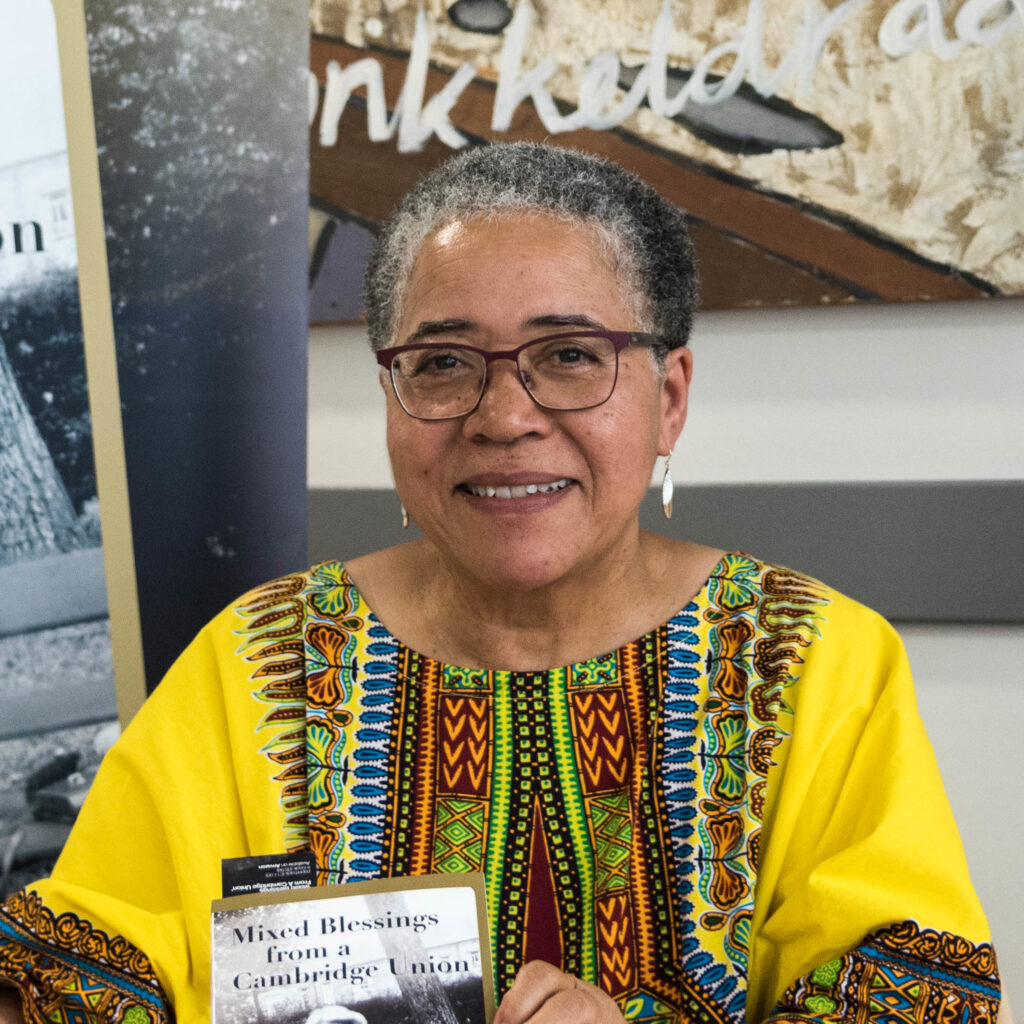

When Britain recently celebrated the 50th anniversary of the first sickle cell nurse specialist in the country, tributes poured in for Dame Elizabeth Nneka Anionwu — the trailblazing nurse, academic, and advocate whose work transformed the understanding and treatment of sickle cell disease in the United Kingdom.

She is celebrated today as a national treasure — an icon of compassion, perseverance, and professional excellence. Yet, behind her glittering honours lies a sobering truth: Nigeria lost a girl whose destiny could have rewritten the story of its healthcare system.

Dame Elizabeth is the daughter of a Nigerian father — a girl whose destiny, if embraced by her homeland, might have changed the trajectory of healthcare in Africa’s most populous nation.

Born in Birmingham in 1947 to an Irish mother and a Nigerian father from Onitsha, Elizabeth’s childhood was one of hardship. She built her career in the UK, Anionwu has never hidden her Nigerian heritage as her father, Lawrence Odiatu Victor Anionwu, was a scholar who became a university professor and later Nigeria’s ambassador to Italy. She met him only as an adult, long after her identity had been shaped by her British upbringing.

Her mother, a student nurse, faced racial stigma and had to place her daughter in a Catholic children’s home. There, Elizabeth endured loneliness, bullying, and the sharp edges of racial prejudice.

One day, at age eight, she received treatment for a painful eczema condition. A kind nurse comforted her — a small gesture that changed her life. “That moment of care stayed with me forever,” she would later recall. “I decided I wanted to be a nurse who made people feel safe and seen.”

Anionwu entered nursing in the 1960s — a time when Black nurses faced severe discrimination. Yet, she persevered, qualifying as a nurse, health visitor, and lecturer. While working in London, she noticed a tragic gap in the system: many families of African and Caribbean descent were suffering from sickle cell and thalassaemia, yet the health service knew almost nothing about these diseases.

In 1979, she helped establish the UK’s first nurse-led Sickle Cell and Thalassaemia Counselling Centre in Brent — a revolutionary step that brought genetic screening, family counselling, and education to communities that had long been ignored.

Her work transformed national awareness of these conditions, influencing both policy and practice.

As Lord Victor Adebowale, CBE, CEO of Turning Point, noted:

“Elizabeth Anionwu has made an enormous contribution to the health and wellbeing of multi-ethnic communities. Her tireless work to ensure that people affected by sickle cell disease and thalassaemia get the support they need has touched thousands of lives.”

Her leadership extended beyond clinical care. In 1997, she was appointed Dean of the School of Adult Nursing and Professor of Nursing at the University of West London, where she established the Mary Seacole Centre for Nursing Practice — a hub dedicated to multicultural healthcare excellence.

Also read UK study confirms local Nigerian plant cures Sickle Cell

She also co-led the Mary Seacole Memorial Statue Appeal, ensuring that the pioneering Jamaican-British nurse who served during the Crimean War was finally honoured in London. The statue, unveiled at St Thomas’ Hospital in 2016, stands as a symbol of recognition for Black nurses who shaped history.

Dame Elizabeth’s honours are many:

Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) in 2001

Dame Commander (DBE) in 2017

Member of the Order of Merit (OM) in 2022, one of the UK’s most exclusive honours.

She is also an Emeritus Professor of Nursing, a Fellow of the Royal College of Nursing (FRCN).

In July 2018, as part of the celebrations for the 70th Anniversary of the National Health Service, Elizabeth was included in the list of the 70 most influential nurses and midwives in the history of the NHS.

Meanwhile, Nigeria bears the heaviest burden of sickle cell disease globally, with over 150,000 babies born each year carrying the condition — many of whom die before their fifth birthday.

Had Elizabeth Anionwu been nurtured in her father’s country, she might have led a revolution in public health. Her expertise in community-based screening, counselling, and genetic education could have dramatically changed outcomes for millions of African children.

Instead, her groundbreaking work flourished in Britain, while her ancestral homeland continues to struggle with poor screening, low awareness, and outdated policy.

Her story is not just personal; it is symbolic of Nigeria’s broader tragedy — the consistent export of excellence. The nation keeps losing its brightest minds to the opportunities and recognition found abroad.

Today, the Nigerian government is beginning to engage talented diaspora professionals such as Tolu Ogunlesi, Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, and Akinwumi Adesina to drive reforms and national development.

It is time for that circle to include Dame Elizabeth Anionwu.

Nigeria’s Ministry of Health, the National Sickle Cell Centre, and relevant agencies should reach out to this extraordinary woman — not merely to celebrate her, but to engage her leadership in designing a continental framework for sickle cell control, genetic screening, and nurse-led community care.

Her vision could help shape a National Sickle Cell Strategy anchored on early testing, awareness, and healthcare equity — the same principles that defined her success in Britain.

By inviting her to consult, collaborate, or even mentor emerging health leaders, Nigeria would be reclaiming a legacy once lost.

Dame Elizabeth Nneka Anionwu’s story is one of triumph, identity, and purpose. It is also a national mirror. While the UK celebrates her as a pioneer, Nigeria must see her as a destiny daughter — one who carries the wisdom to heal the home she never truly knew.

In her triumphs, Dame Elizabeth Anionwu has spoken of unfinished work. In interviews, she has described continued inequities in care for sickle cell patients, challenges faced by Black nurses in professional progression, and the need for curriculum reform in nursing to include marginalized histories.

Her own memoirs, Mixed Blessings from a Cambridge Union (later reissued as Dreams From My Mother), delve into the traumas of her upbringing, the search for identity, and the resolve to channel hardship into purpose.

She once turned down an early honour in the 1980s, believing that recognition without structural change was hollow.

Despite her global acclaim, Dame Elizabeth Anionwu has never forgotten her roots. She embraces her Nigerian name, “Nneka,” meaning “Mother is supreme.” In interviews, she often speaks with affection about her heritage and expresses hope that her work can inspire healthcare reform across Africa.

In her quiet dignity lies a challenge to every African government: create a country where brilliance is not exiled.

For if Nigeria had kept its Anionwus, there might be fewer graves of sickle cell children — and more nurses changing the world.